New survey data from the Betsy Lehman Center add to the growing evidence that talking to a peer helps alleviate the detrimental stresses that clinicians and staff experience after involvement with a difficult event in patient care.

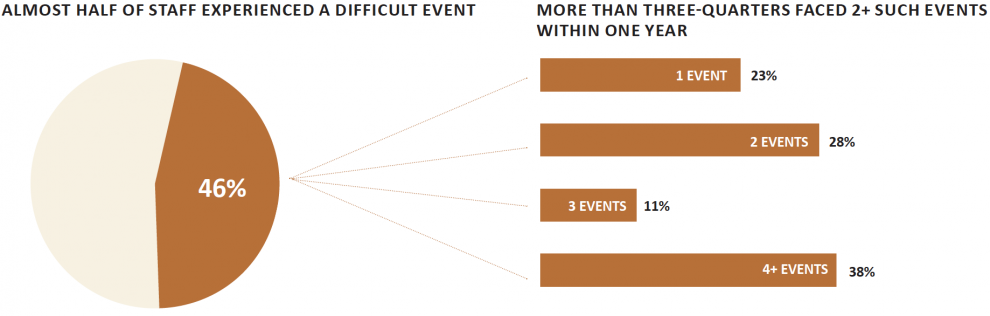

The data, collected from select units such as intensive care and emergency departments in seven hospitals across the state, also showed that nearly 1-in-2 health care personnel experienced at least one difficult event in a 12-month period, with some reporting four or more such events. Personnel included not just doctors and nurses, but other clinical and non-clinical staff such as members of administrative, transport, security, and other teams.

Survey findings offered insight into difficult event experiences including:

- Frequency: 46% of clinicians and staff experienced a difficult event in the prior year, as did nearly one-third of associate practice providers and other clinical staff, along with 53% of security, 24% of administrative and 46% of other non-clinical staff. Of those who experienced a difficult event, 77% reported two or more such experiences within a year.

- Emotional impact: Only a small fraction of respondents said they experienced no emotional fallout from the difficult event that occurred. In fact, 60% said they were sad afterwards, 34% reported frustration and 31% anxiety. In addition, 41% lost sleep after the event and 33% of clinical and 28% of non-clinical staff said they experienced a loss of joy from their work. Several of the impacts, including frustration and anxiety, could persist for many months.

- Coping: The most common approach to managing emotional and other consequences from a difficult event was to talk to someone else. Of that group, 73% turned to a peer. Talking to a peer “definitely helped” 77% of those who used that coping strategy and another 27% thought it “probably helped.” And, among respondents who had not recently experienced a difficult event, 66% suggested their strategy would be to talk to someone else.

These findings align with other work demonstrating that engaging in conversations with colleagues is a common and helpful approach to coping with emotions that arise after difficult events in patient care.

The seven hospitals surveyed are participating in a pilot program initiated by the Betsy Lehman Center to offer peer support to personnel affected by difficult events in patient care. Each participating hospital selected two units: one to institute a peer support program and one to serve as a control unit. None of the participating hospitals had prior experience with peer support programming.

“Having local data helps us make the case for peer support programs not only at the pilot hospitals but at health care organizations throughout the state,” says Linda Kenney, Director of Peer Support Programs at the Betsy Lehman Center. “I am thrilled to be doing this work with other members of our peer support team as well as our hospital partners.”

The findings are compiled in a new report, Difficult events in patient care impact all staff, but support from peers can help, which describes the impact of such events as well as coping mechanisms used by health care workers. Examples of difficult events cited by the survey respondents included: unexpected patient death, challenging interaction, death of a patient the respondent had bonded with, medical error, or feeling blamed for an event.

A complementary survey of C-suite and unit leadership in the hospitals offers additional insight that can inform the implementation of successful peer support programs. For example, leadership may need help recognizing the extent of their staffs’ experience with difficult events. Only 10% of leadership had an accurate assessment of the number of staff impacted by difficult events. Most of the rest either underestimated the extent of staff experiences or were unable to hazard a guess. Four-in-10 leaders assumed that staff took time off from work in the aftermath of an event, but almost all staff who reported experiencing an event said they did not modify their schedules. Asked about existing resources that might help clinicians and staff cope with a difficult event, nearly half of staff and about one third of leadership said they were not aware of any such resources.

The pilot peer support program initiative is part of a larger effort by the Betsy Lehman Center to address the emotional needs of health care professionals, staff, patients, and families.

“We know that everyone can be deeply affected when something goes wrong in a patient’s care, including clinicians and staff,” Kenney says. “We’re very committed to helping make sure peer support services are widely available and effective to help individuals cope with difficult feelings by turning to a trusted colleague.”